Resistance Training (RT) means the use of some form of resistance against muscular actions of the body. Commonly this can involve free weights, such as dumbells or kettlebells or weights machines such as leg press, leg extension or hamstring curl.

RT and distance running haven't always had an easy relationship. Many people believe that RT isn't helpful for distance runners and can even have a negative impact on performance. Some go as far as saying “performing weights using a machine should NEVER be done by any runner.”

The arguments against RT usually centre around a few points suggesting it isn't functional, can negatively affect performance and may reduce activity of stability muscles. These arguments may be valid but I've never seen them presented with any research evidence to support them.

Regular readers might remember we had a similar issue with the use of sidelying exercises for glutes. A number of people are adamant they shouldn't be used for rehab despite extensive research showing they have a role. This appears to be the case with RT, and once again I would urge people to remember that nothing is set in stone with physiotherapy or exercise science. As soon as you declare something to be an absolute certainty someone will find evidence to the contrary. I think it's important to be relaxed in your opinions and open to the ideas of others. To that end, I would recommend you read the article that the quote above comes from. That way you can see both sides of the debate and make an informed decision.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) recommends RT for endurance athletes;

“Intelligent use of the weight room, just like intelligent implementation of a running program, can have a dramatic influence on the success of the competitor. This success can be defined as faster running times, but can also be extended to include reduced injury risk, and an overall heightened enjoyment of the sport, a goal that many athletes surely have.” Erikson 2005

More evidence for the use of RT comes from excellent articles by Jung (2003) and Jones and Bampouras (2007 summary only). Their reviews of the literature will form the basis for our conclusions here.

We'll look at the effect of RT on a few key factors in running VO2 Max, lactate threshold, running economy, injury prevention and injury rehab.

VO2 Max

VO2 Max is the maximal capacity of an individual's body to uptake, transport and use oxygen during exercise. It is often used as a measure of physical fitness, more details available here.

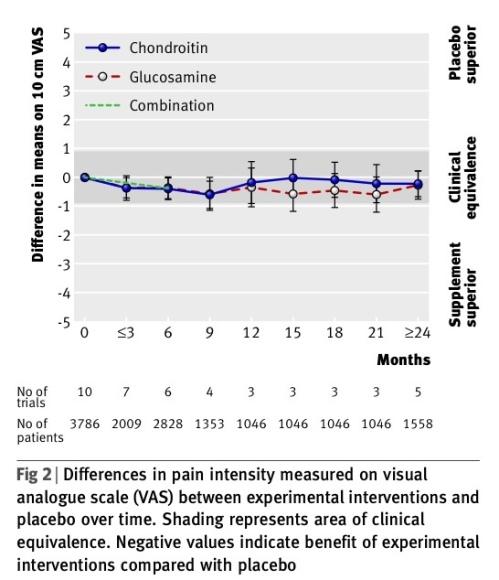

Research has concluded that RT is unlikely to increase VO2 Max in trained individuals but also has been shown not to decrease it. I.e. while it might not help, it doesn't hinder.

Lactate Threshold

Lactate threshold isn't easy to describe. This very useful article defines it as “the fastest pace you can run without generating more lactic acid than your body can utilize and reconvert back into energy”

There wasn't a great deal of research into RT and lactate threshold. 1 study showed an increase in untrained individuals but no change has been shown in distance runners. Once again RT was shown not to have a negative impact.

Considering the nature of RT we wouldn't expect it to improve VO2 Max or lactate threshold in trained individuals. RT is not usually an activity that involves prolonged periods of exercise with high demands on the cardiovascular system. Instead it usually requires bursts of activity placing muscles under load. We wouldn't expect it to improve cardiovascular fitness and the research appears to have confirmed this.

Running Economy

Running Economy is how efficiently a person uses oxygen while running at a certain pace. It is a measure of running efficiency, a little like how much fuel a car would use at a certain speed. Imagine I asked you to run with a fridge on your back, it would drastically reduce your running economy but your VO2 max wouldn't change. You'd still be as fit physically, but you'd run a lot slower due to very poor running economy. On the upside, you could stop occasionally and snack on something from the fridge!

RT has been shown to improve running economy and Jones and Bampouras (2007) point out that there is a strong association between running economy and distance running performance.

The exact mechanism by which RT improves running economy hasn't been defined but there are several theories on how it works. A short version is this – resistance training improves muscle strength, neurological characteristic and 'stiffness' resulting in more efficient use of energy with every footfall. For the more technical amongst you it is thought to affect the Stretch Shortening Cycle improving efficiency of translation of ground reaction force into forward propulsion.

Thinking about it from a more common sense point of view, imagine if your legs were so weak you could barely get up from a chair, you wouldn't be able to run very well at all. Now imagine they are so strong and muscular that you look like Arnie in the 80's and your thighs are visible on GoogleEarth, you'd struggle to run then too! Somewhere there is a middle ground, an optimal amount of strength for the running you do.

Injury Prevention

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly there is a lack of research on the use of RT in injury prevention in runners. Fields et al. 2010 commented that, “there are no prospective, primary prevention studies in runners” in their review of the research underlying the prevention of running injuries. They went on to conclude,

“In spite of numerous studies, strong evidence for prevention of running injury exists only for controlling training errors primarily by limiting total running mileage…While studies of strength, biomechanics, stretching, warm-up, nutrition, shoes, and psychological factors all raise intriguing questions about both the etiology and the prevention of running injuries, strong evidence that modifying any of these will prevent running injury requires further research.”

It makes sense that improving strength should reduce injury risk but we just don't have the research to back that theory up yet. Maybe it's because training error, particularly doing too much, is such a common cause of injury that adding in more exercise (in the form of RT) doesn't always help the situation. Fitting RT within a busy training schedule without impacting upon the quality of other workouts can be a challenge, we'll touch on how to manage this shortly.

Injury rehab

I feel RT has perhaps its biggest role here. Away from research for a moment, experience tells me that resistance training can be hugely beneficial when used as part of a comprehensive rehab programme. I've run lower limb rehab groups for over a decade and seen countless patients improve with progressive resistance training including free weights and machines.

We combine weight machines such as leg press, leg extension, hamstring curl and hip abduction/ adduction with squats, single leg dip, calf raises and lunges. We add balance and control exercises on rocker boards, wobble boards, BOSU's, trampette and balance cushions. We use agility and sport specific drills with ladders, cones and hurdles and add in plyometrics and multidirectional stability work. We make cardiovascular fitness part of the programme and get people running, cycling, rowing or cross training. RT isn't all of the rehab programme but certainly can be an important part of it.

We've talked before about the big three strength, balance and flexibility and how important they are in limb function and running. There is a wealth of research showing how RT can be used to develop the first of the big three, strength. Indeed tweaking of your resistance training allows you to target specific goals within the broader category of strength, including power, endurance and hypertrophy (increasing muscle size).

What your goals are post injury and how you use RT to achieve them will depend on the injury itself and what deficits you have. Identifying these weaknesses usually requires some help from a Physio or sports therapist. I would recommend having some guidance before embarking on a resistance programme to rehab an injury as it is easy to aggravate a problem and it's more effective when used to target specific problem areas. Resistance Training should be pain free, and I would recommend a gradual increase in resistance if rehabbing and injury.

Practicalities – how should I use RT?

As mentioned above RT is most likely to be effective if used to strengthen areas of weakness, rather than a scattergun approach of a bit of everything. That said, common weak areas include calf, quads, hamstrings and glutes and all of these can be targeted with RT. In the coming weeks we will be adding videos to the blog on how to 'blitz' some of these muscles with 3-5 minutes of intense exercise.

When introducing a RT programme it is best to do it slowly, with gradual increase in load and frequency. Ideally RT should be done at least twice per week although you will see changes with a once weekly session. Allow at least 8 hours between running and then doing resistance training, ideally have a 24-48 hour gap. The research is less clear on doing resistance training and then running, I would suggest a similar 24-48 hour gap if possible. Running on legs that are recovering from RT is challenging and can risk injury. So a weeks schedule could be;

Monday rest Tuesday run Wednesday RT Thursday run Friday RT Saturday rest Sunday long run.

The long run is 'bracketed' by rest days and you have 24 hours between running and RT. Juggling running 5 or more times per week with RT is a real challenge. You may need to be doing both in the same day, if so consider doing one morning and one in the evening to allow at least 8 hours and choosing that day to do a recovery run rather than interval or hill work. Erikson (2005) and Paul and Bampouras (2007) both include upper limb strengthening in their RT programme, this could be done more easily on days when running and RT are combined.

Realistically for many runners, especially those of us with jobs, families, partners etc a once weekly RT session is more realistic. Hopefully the 'blitz' videos will provide a way of doing strength work in a short period of time to make it more feasible.

What about repetitions (reps), sets and loads?

This is a vital, and often neglected part of RT. Like choosing which muscle group to work on, selecting reps, sets and loads should ideally be based on specific deficits. There are 4 main categories strength, power, hypertrophy and endurance. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) produced these guidelines which form the basis of the recommendations below;

Strength is about production of force, plain and simple. Building strength is increasing the force a muscle group can produce. To build strength do 8-12 reps using a moderate to heavy load (so the final 2 reps are challenging and you probably wouldn't manage an extra rep) do 3 sets each separated by a rest period of 2-3 minutes. Increase the load by 2-10% when you can manage 1-2 reps above your target e.g. If you're aiming for 12 reps with a certain load but can do 14. Strength work often forms the basis of power, endurance and hypertrophy training. Although distance running is an endurance event it may be that building strength with RT will be more appropriate for some runners, as mentioned before it will depend on the individual.

Power is closely related to strength but time becomes a factor. Power is essentially strength divided by time. A good example of power is Olympic Weightlifting – a huge weight is lifted at high speed. You'll need adequate strength before attempting power work so it's often best to work on strength first. When building power start with low to moderate weight and gradually build to heavy loads. Do 3-6 reps with an 'explosive tempo' I.e. quickly! 1-3 sets with a rest period of 2-3 minutes between each.

Hypertrophy means increasing muscle bulk. This is particularly useful if you have had an injury that resulted in muscle atrophy (reduction in muscle size). Again a basic level of strength is needed before doing hypertrophy work. There is some cross-over between the two and strength work is likely to result in some increase in muscle bulk. Initial loads and reps are similar to strength – 8-12 reps with moderate to heavy load, 1-3 sets separated by 1-2 minute rest period. This may progressed to heavier loads 1-12 reps (depending on load) 3-6 sets with a 2-3 minute rest period.

Endurance is how well a muscle produces the same amount of force when asked to continue to do so for a prolonged period of time. Use light to moderate loads, 15-25 reps, multiple sets (start at 2-3 and build up) with a 1-2 minute rest period between sets. I aim to fatigue a muscle group with endurance work, so the load you use should be sufficient to do that within 15-25 reps.

Reps and sets are somewhat redundant unless load is considered. Reps and load come together in something called Repetition Maximum or Rep Max (RM). 1RM is the maximum load you can lift once with good technique. 10RM is the maximal load you can lift 10 times with good technique. The load for 10RM will obviously be lower than 1RM. To work out 10RM pick an exercise and gradually increase the load until you find the amount you can lift 10 times (but couldn't manage 11). Just to confuse you, the loads recommended by research are often presented as a percentage of 1 rep max. I have included these and the details above in a table below for those that want that level of detail. For the rest of us, it's usually about lifting the heaviest load you can manage for the amount of reps you're doing, while maintaining a good, pain free technique.

The exact percentage of Rep Max and reps and sets recommended for strength, power, hypertrophy and endurance are subject to much debate. The guidelines from the ACSM looked at over 250 studies to produce their recommendations, despite this even their conclusions have been questioned. I'm very open to suggestions on reps, sets etc please feel free to put them in the comments section. What I have presented is a rough guide based on recommendations in research. Erikson's paper includes a sample RT programme including sets and reps as does Jones and Bampouras (if you can access it).

The ACSM make a host of other recommendations including that a mixture of free weights and machines are used and that concentric, eccentric and isometric work is included. For further details see their paper, linked above.

Study Limitations

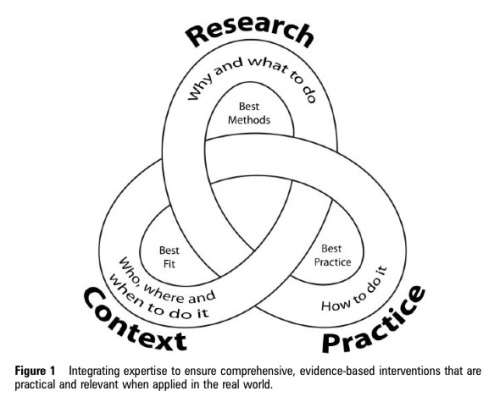

There are limitations to the findings from the literature, as ever. Jung (2003) points out a sparcity of evidence showing improved race time as a result of RT. The methods used vary considerably, with some studies incorporating plyometrics as well as resistance training. A key point too is the population they have studied, again they varied from untrained individuals to elite athletes, although most were done in trained individuals (as measured by VO2 Max). One group that appears to be missing is injured runners, most of this work is done on 'healthy' subjects. The research done on injured individuals is often a) not specific to runners or b) involves a mixture of treatment approaches which may include RT. Even then research is seldom totally conclusive and there is a limitation in research itself – it's designed to allow you to apply a treatment approach or physical test to a certain population and yet, even within that population, people are incredibly different.

Even with a fairly specific population you'd have difficulties. If you studied runners, with patellofemoral pain syndrome between 20 and 40 years old, with no signs of arthritis on X-ray and you treated with resistance training you might only expect 30-40% to improve. Why? Because some will have it from over training, some from control issues, some with biomechanical problems, some with tissue flexibility issues etc etc. It's unlikely that research done is this manner will make definite conclusions.

Luckily though, we don't make decisions solely on research, we can use experience and learning too. It's often said as people we are each an experiment of 1 – see what works for you that's the key.

Final thoughts: Resistance Training has the potential to improve running economy and performance. It has long had a role in injury rehab and is likely to have one in injury prevention. The research reviewed here did not find that RT had a negative impact on VO2 Max, lactate threshold or running ability.

RunningPhysio recommends that you see a health professional prior to starting a resistance training programme to help you identify specific deficits. This can make RT more effective and reduce risk of injury.